Scientists are proposing a new periodic table, which is flight

The periodic table of the elements, mainly created by the Russian chemist, Dmitry Mendeleev (1834-1907), I celebrated it 150th anniversary last year. It would be difficult to overestimate its importance as an organizing principle in chemistry – all budding chemists become familiar with it from the earliest stages of their education.

Given the importance of the table, one might be forgiven if they think the arrangement of the elements is no longer up for debate. However, two scholars in Moscow, Russia, published a Proposal for a new order.

Let’s first think about how to develop the periodic table. By the late eighteenth century, chemists were clear about the difference between an element and a compound: the elements were chemically indivisible (examples being hydrogen and oxygen) whereas compounds consist of two or more elements together, and have completely different properties from the constituent elements.

By the early nineteenth century, there was Good circumstantial evidence For the presence of atoms. By the 1860s, it was possible to list the known elements in order of their relative atomic mass – for example, it was hydrogen 1 and oxygen 16.

Simple menus are, of course, one-dimensional in nature. But chemists were aware that some of the elements had somewhat similar chemical properties: for example lithium, sodium and potassium, or chlorine, bromine and iodine.

Something appears to be repeating, and by placing chemically similar elements next to each other, a two-dimensional table can be constructed. The periodic table was born.

More importantly, Mendeleev’s periodic table was derived experimentally based on the observed chemical similarities of certain elements. A theoretical understanding of its structure would appear only in the early twentieth century, after the structure of the atom was established and after the development of quantum theory.

The elements are now arranged by atomic number (the number of positively charged particles called protons in the nucleus of an atom), not by atomic mass, but also by chemical similarities.

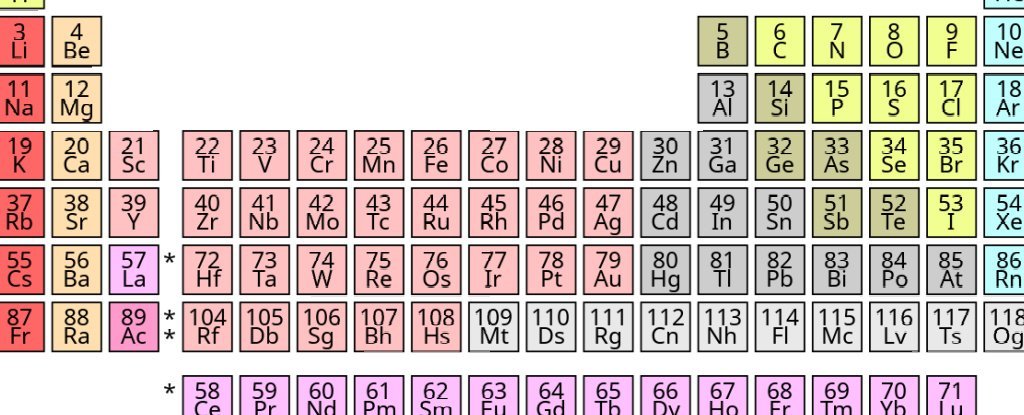

But the latter now follows the arrangement of repeating electrons in so-called “shells” at regular intervals. By the 1940s, most textbooks had a periodic table similar to the one we see today, as shown in the figure below.

Today’s periodic table. (Offnfopt / Wikipedia)

It would be understandable to think that this would be the end of it. But this is not the case. A simple internet search will reveal All kinds of versions From the periodic table.

There are short versions, long versions, round versions, spiral versions, and even 3D versions. Many of these, to be sure, are simply different ways of conveying the same information but there are still disagreements about where to put some of the elements.

The precise placement of certain elements depends on the specific characteristics we wish to highlight. Thus, the periodic table that prioritizes the electronic structure of atoms will differ from the tables whose main criteria are certain chemical or physical properties.

These versions do not differ much, but there are certain elements – hydrogen for example – that one might place very differently depending on the specific characteristic one would like to highlight. Some tables place hydrogen in Group 1 while others are at the top of Group 17; Some even have tables In a group on their own.

But more fundamentally, we can also think of arranging the elements in a completely different way, one that doesn’t include an atomic number or reflects an electronic structure – by going back to a one-dimensional list.

new offer

Last attempt to arrange items this way It was recently published in The Journal of Physical Chemistry By scholars Zahid Lahiari And the Artem Oganov.

Their approach, Based on the previous work of others, Is to assign the so-called Mendeleev number (MN) to each element.

There are several ways to derive such numbers, but the latest study uses a combination of two basic quantities that can be measured directly: the element’s atomic radius and a property called Electronegativity Which describes how strong an atom is to attract electrons to itself.

If an element orders their MN, then their closest neighbors, unsurprisingly, the MNs are somewhat similar. But more importantly, is to take this step forward and create an MN-based two-dimensional network of the components of so-called “binary compounds”.

These are compounds that consist of two elements, such as NaCl, NaCl.

What is the benefit of this approach? Most importantly, it can help predict the properties of binary compounds that have not yet been synthesized. This is useful in researching new materials that are likely to be required for both future and current technologies. Over time, no doubt, this will extend to compounds containing more than two components.

A good example of the importance of searching for new materials can be appreciated by looking at the periodic table shown in the figure below.

This table not only illustrates the relative abundance of items (the larger the box for each item, the more there is) but it also highlights potential sourcing issues related to technologies that have become ubiquitous and fundamental in our daily life.

Take cell phones, for example. All items used in its manufacture are identified by phone code and you can see that many of the ordered items are becoming scarce – their future supplies are uncertain.

If we were to develop alternative materials that avoid the use of certain elements, the insights gained from arranging the elements by their MNs may be helpful in this research.

After 150 years, we can see that periodic tables are not just a vital educational tool, they remain useful to researchers in their search for new essential materials. But we should not think of the new versions as alternatives to the previous graphics. The presence of many different tables and lists deepens our understanding of how objects behave.

Nick NormanProfessor of Chemistry University of Bristol.

This article was republished from Conversation Under a Creative Commons license. Read the The original article.

Communicator. Reader. Hipster-friendly introvert. General zombie specialist. Tv trailblazer