Harbin’s skull probably belonged to a new species of human, Homo longi

“It contrasts with everything we have learned in the last ten years.”

The skull of a fugitive man was found in a Chinese cave

Coil: Kai Jing, Chuang Chao

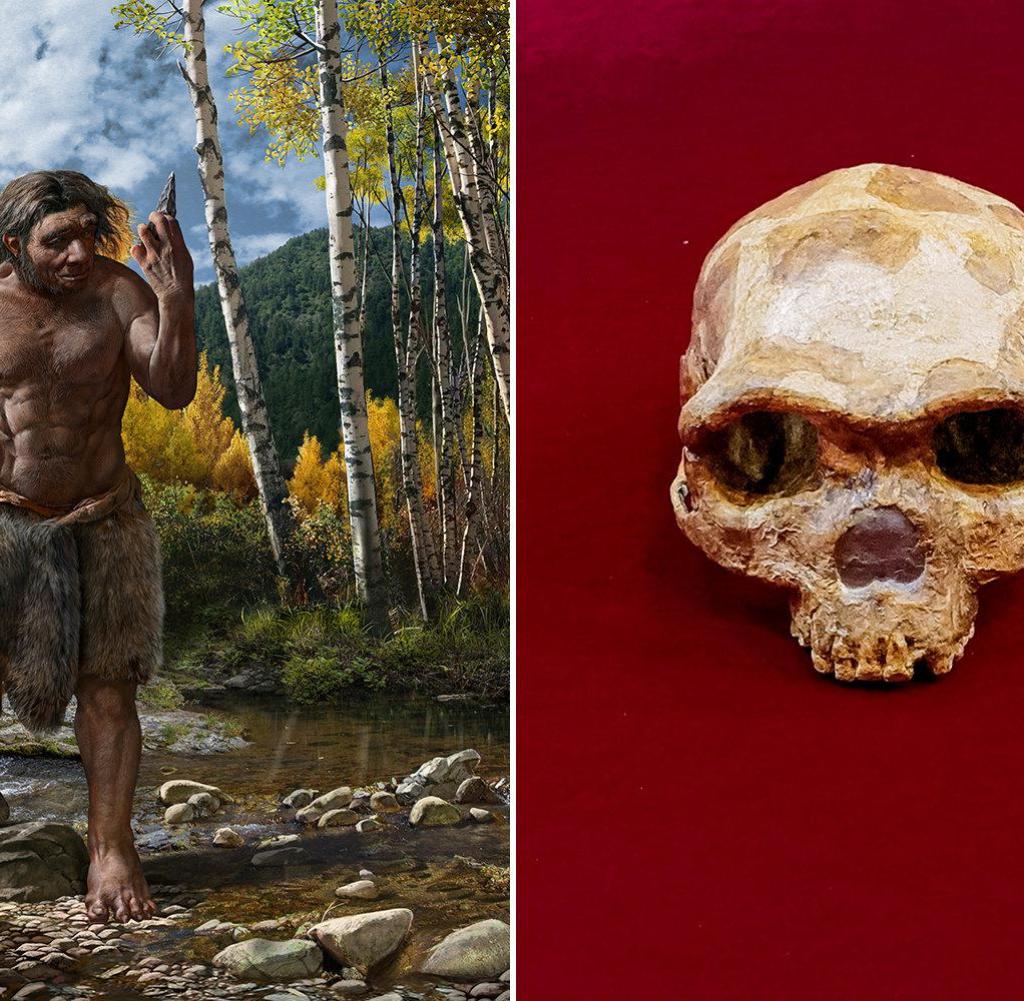

Neanderthals have been considered the closest relative of modern humans to extinction: but evolution is complicated, new studies show: the “Harbin skull” probably belonged to a new species of hominid, “Homo longi”. What does this mean for us?

eThe skull found in China could belong to a human lineage more closely related to modern humans than to Neanderthals. This is the result of an international research group led by Xijun Ni and Qiang Ji from Hebei Geo University in Shijiazhuang (China). Scientists even described the fossil in the journal Innovation as representing a new species of hominid.

However, this assessment will spark debate, says Jean-Jacques Hublin of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig.

Comparison of skulls: Beijing, Maba, Jinniushan, Dali, Harbin (from left to right)

Coil: Kai Jing

The skull was found in 1933 while working on a bridge in the northern Chinese city of Harbin, but only a few years earlier it was given to scientists by the descendants of its discoverer. “The Harbin fossil is one of the most complete skull fossils in the world,” the newspaper quoted Jie in a letter from the magazine. The skull has preserved many anatomical details necessary to understand the evolution of the human race and the origin of Homo sapiens.

The researchers discovered both ancient and modern features of the skull: the skull’s volume of 1,420 milliliters is comparable to that of humans today, and the short, flat face with small cheekbones is more compatible with Homo sapiens. On the other hand, according to the researchers, the elongated and flat hat, strong bulges above the eyes, deep eye sockets and large molars are more reminiscent of older people. “Overall, the Harbin skull gives us more clues to understand homologous diversity and the evolutionary relationships between these different human species and populations,” Ni says.

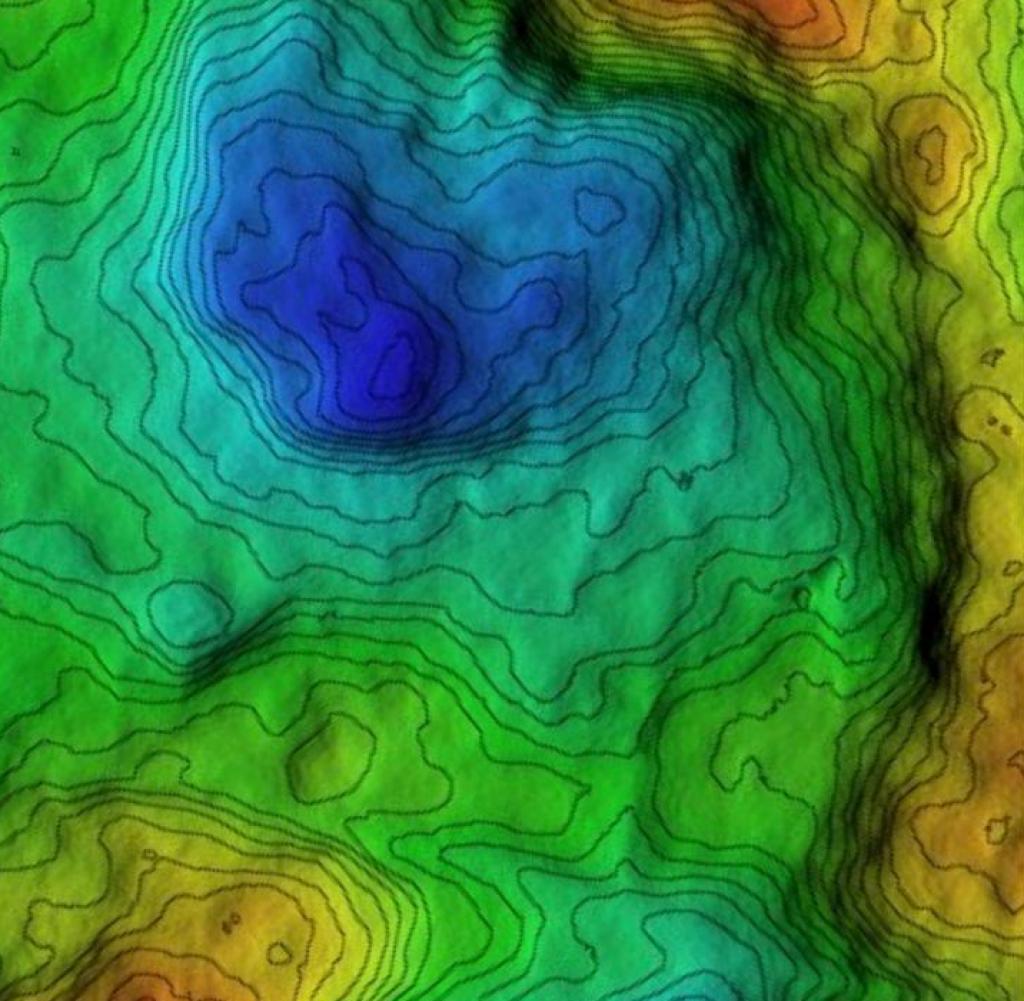

The scientists examined small deposits of earth on the skull as well as soil at the exact location. They found good agreement and determined an age of between 138,000 and 309,000 years for the corresponding terrestrial stratum through geochemical investigations.

Dating uranium and thorium indicates an age of at least 146,000 years. Accordingly, the Harbin man could have been a contemporary of the archaic people of today’s China, whose bones are found in Xiahe (age: at least 160,000 years), Jinyushan (at least 200,000 years old), and Dali (240 thousand to 327 thousand years ago). year) and Halong-dong (265 thousand) to 345,000 years old).

From their genetics analyzes, Ni, Jie and colleagues conclude that said fossils belonged to a group of people more closely related to Homo sapiens than to Neanderthals. The researchers wrote that because China stretches across so many climatic zones, these people must have been highly adaptable.

“Our analyzes also suggest a possible link between Harbin’s skull and the mandible Shikha, a fossil attributed to the Denisova lineage,” said one of the three studies.

However, part of the research group announced that the Harbin skull belonged to a new species of human, “Homo longi” (“dragon man”), named after the geographical name of Longjiang of the province in which it was found.

This classification received little understanding from the anthropologist at Leipzig-Hüblin: “It goes against everything we have learned in anthropology in the past ten years.” Although not all research results are accessible, he says, based on the publication studies assume that the Harbin man, like many other human discoveries from China, is a Denisova man.

The remains of the Denisova people were found in the Altai Mountains of Central Asia and in Tibet, traces of the genetic material of the Denisovans were found in various peoples of East Asia and Australia. Denisovans are referred to as a sister group to Neanderthals, and the discoverers did not classify him as a separate human species at the time.

Communicator. Reader. Hipster-friendly introvert. General zombie specialist. Tv trailblazer